First published to accompany Beatriz Olabarrieta’s solo exhibition The only way out is in at Sunday Painter, London.

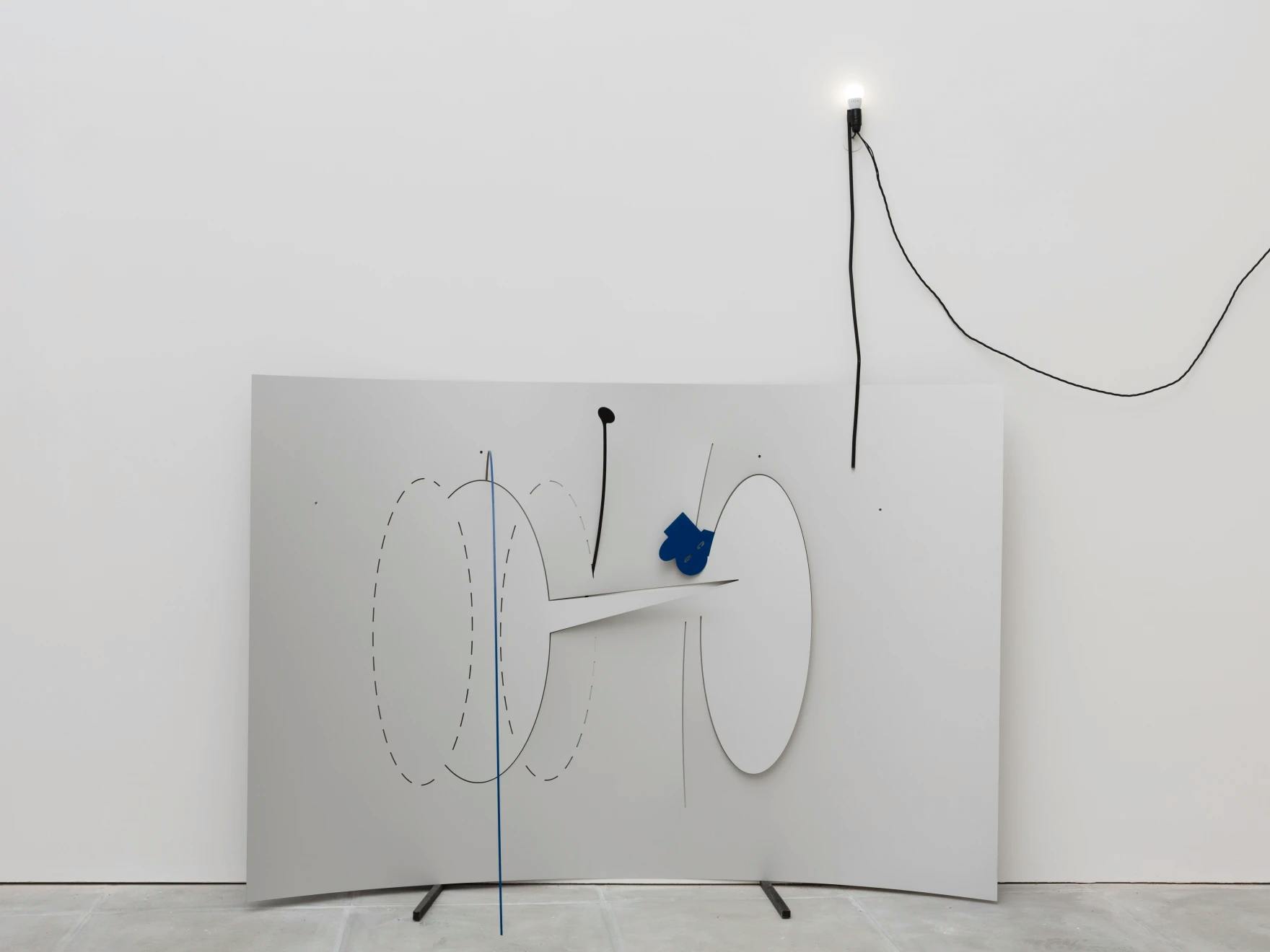

Beatriz Olabarrieta, Now we are talking (brother), 2017, Laminate, spray paint, steel rod, light bulb, cable, tape, 122 x 185 x 14 cm

Reading time 6'

I’m sitting at a table on a chair that is too stiff in an office that is too warm, connected to the world outside by an old computer, telephone, mobile and window onto the street below. A neglected fax machine lies in the corner. I’ve got no idea where the router is but the internet connection is weak and my various attempts to email and download images are slow and glitchy. I switch between writing emails, an essay, and posting images on Instagram in moments of extended lethargy. I try and match the tone of my writing to the platform, moving from first to third person, personal to more formal address. Some words will find a home in press releases and magazines read by people I’ve never met. Some words will be read by colleagues and friends. Other bits of writing will find no audience. There are words that get silenced in the mouth before they ever have a chance to leave it and words that wait patiently to find their home in sentences as thoughts that need to be herded into action.

Beatriz Olabarrieta’s work is all about communicative errancy — the space of misbehaving words and images. She makes installations with text, objects and images where each component retains a certain elasticity. Rarely anything is fixed or glued. The work has a literal and metaphorical mobility. Speech is (mis)translated into textual and material acts, and there is a conversational and sociable tone between the various components in her installations. The sculptures are logographic and diagrammatic, continually pointing outwards to other things. There is a lexicon of simple and suggestive shapes. The profile of a face and onomatopoeic forms. The installations are often accompanied by sounds that merge static, and somatic references. The body belches and breathes as do the sculptures. There is a constellatory quality to the work with elements pushed to the edge of legibility.

Often using thin sheets of melamine, she bends and folds it, cutting into the material to create gaps and holes that she stuffs with images and material as well as textual fragments. There is a sense of imminent slippage — of things falling down, and failing. Messages that fail to find their recipient, messages with too much noise and messages that are productively misunderstood. The sculptures are like glyphs, desperate to speak yet hyperventilated or dyslexic. I’m reminded of speech bubbles from the 19th century, where visual depictions of talking rise like gas or smoke from the subject, enveloping the surrounding area. Words are like a noxious gas, infecting the ears and minds of closely assembled bodies.

From the early 20th century onwards the depiction of speech bubbles have become standardised and codified, disembodied from the subject. If everything in the graphic image obeys the laws of gravity, the speech bubble has no weight. Words are intended as pure semantics, operating as symbols with no physicality.

In Meso American Art (around 650 AD), speech glyphs are visualised as a type of textual vomit projecting out of someone’s mouth. The shape and colour denotes the timbre of someone’s voice and there is a similar attempt in Beatriz’s work to combine the physicality of the body with the words that come out of it. A thought bubble, unlike a speech act, is represented as a cloud-like shape that looks like a headless sheep. A raised voice is articulated by a series of spikes as if the words physically penetrate the space of reception with the force of transmission. A whisper is often drawn with a dashed line which does a good job of visualising a particularly precarious message. Beatriz’s work performs a type of onomatopoeia and she elides the various communicative registers — merging oblique statements and direct calls for action, errant and well behaved words.

While speech is projected outwards from the body — thoughts tend to coalesce. If speech is perhaps more like a line of flight, a thought is spiral-like, folding the body with its surroundings. A thought puts memory into conversation with knowledge.

I sit in silence at this desk, surrounded by networked objects. Invisible and physical circuits, inputs and outputs, lines of potential flight and spirals of thought. I think about the contours of furniture that fit with ease around the body and others that don’t. I think about how in Beatriz’s work these sound waves and electrical circuits are often materialised — the elements in her installations agitate and irritate each other. I think about melodies and rhythm, about sculptures that are like baselines and images that are like choruses. I think about the background din that accompanies me while I write this essay — radio static, an empty coffee machine gurgling away, a droning fridge, voices on the street below. I think about how buildings are constructed around the voice. At opposite ends of the acoustic spectrum, churches are built acoustically around singing and schools are insulated so that they are conducive to speaking. Words and voices are continually herded around spaces.

In 2015 I worked with Beatriz on an exhibition in Sunderland. One day while sat at my desk much like the one I describe in the opening paragraph, an elderly woman came and knocked on my door wanting to talk about the show. I explained that the exhibition was a bit like an organism rather than a series of static, autonomous objects. The woman pulled a mobile phone out of her pocket and showed me images of her lovingly maintained garden. She pointed at the manicured flowers and hedge, describing it as a live composition. Of course, a flower, depending on the season, moves in and out of legibility. A garden can mean something in summer and something else in autumn. A flower is an organism with inputs and outputs including roots that soak up water, leaves for absorbing the sun’s rays and seeds awaiting pollination. It is an organic space of transmission and reception, and this horticultural metaphor seems apt when thinking about Beatriz’s installations. Artist as gardener and pollinator, Beatriz irrigates as much as installs her work, cultivates as much as exhibits it.