Writing

Intoart

The following texts were commissioned by Intoart, London, an organisation that supports artists and designers with learning disabilities. I was Writer in Residence for Intoart over 2021-23 leading workshops with artists and co-developing interpretation for two major exhibitions over this period. The following texts accompanied the exhibitions 'An Octopus with Boomerangs' (2022) and 'A Lion in the Studio' (2023) at Copeland Gallery, Peckham.

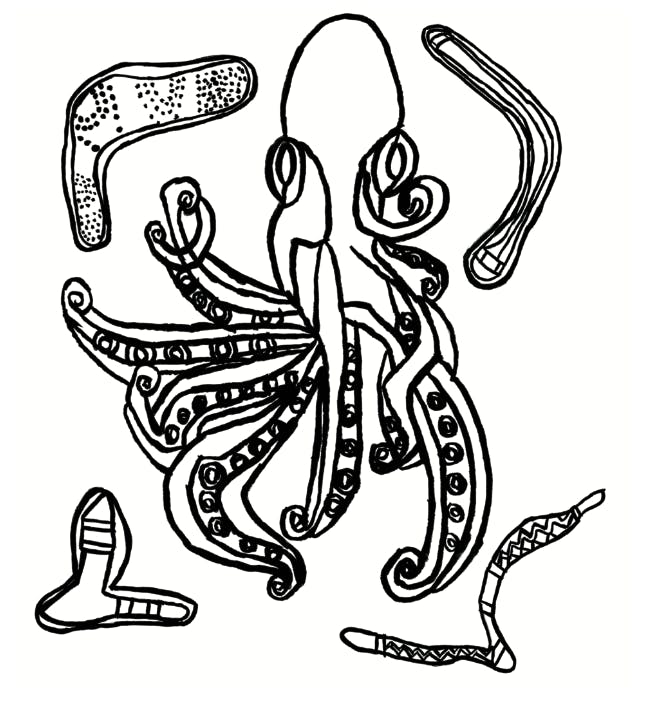

Octopus with Boomerangs by Ntiense Eno-Amooquaye

Reading time 20’

An Octopus with Boomerangs

Making Boomerangs: Love Letters...

A roomful of artists are beavering away. The sound of drawing and painting provides an insistent rhythm and is accompanied by intermittent bursts of chatter. A boiling kettle provides a whistling crescendo. Everyone is rapt and attentive. The tea turns cold waiting for the parched lips of distracted artists. A ravenous bin in the corner of the room squats Pac-Man-like attentively awaiting its next meal of discarded drawings.

Piles of paper await the artists’ attention. Stacks of completed canvases impatiently wait for the public’s scrutiny. Pictures of landscapes and portraits adorn the walls. The early afternoon light illuminates a dusty pot plant on the window sill. Pigeons merrily chirrup through the open window.

The artists are occupied — deep in creative flow — drawing faces with elongated and squashed features: smiles where eyes normally are and ears that look like musical instruments. Human anatomy becomes lightly anarchic, treated like Play-Dough: torn apart and reassembled at will. These painted and drawn figures form a surrogate community, ready to jump off the page and march into the world with a set of lengthy demands. What have they got to say? Who will listen?

Motifs echo across artists’ works: a cocktail of influences drawn from design, art history, TV and Google image searches. Someone is preparing for an exhibition, another artist is making a scarf. Somebody else is making a dress to wear at her performance. Little distinction is made between the various approaches. All materials and themes are available: a painting of a plane crash? Hell yes! Watercolours of the English football team? Why not Raheem Sterling’s slaloming runs are works of art after all.

The artist Andre Williams is rendering extravagant interiors in fine multi-coloured pen. He furnishes his drawings with oversized chandeliers that dwarf the sofa and a fireplace that engulfs the brightly hued room. It’s a home fit for an aristocrat with a penchant for mid-Eighties Memphis design. Many of these drawings are further expanded into physical interiors.

Ntiense Eno-Amooquaye writes down lists of words and cuts them up into lyrical shopping lists. Art Deco Zebra Crossing. Showing the Words of an Outside. The phrases teeter on the edge of legibility — desperate to be read aloud. Both artists have an interest in letters and the shapes they make. Eno-Amooquaye performs the poems dressed in clothes she designs framed by scenography she makes. Like all artists in the room, she’s a world-builder and a dream-maker, translating her experiences through her own inimitable vision.

Eno-Amooquaye’s work is indirect, focusing on ornamentally and sensuality. She picks words she enjoys reading out, sucking on their cadences like sweets, and letting their melodies ring out.

These works remind me that loving something is a good reason to make art about it. All artworks — at some level — are declarations of love. In art, love is often dismissed as superficial — naff even — but, of course, it isn’t. Love requires more effort than anger and a declaration of love always contains an act of criticism: putting what we want into the world is a way of saying what we don’t want.

Intoart is an Octopus...

Contrary to our modern understanding, art studios — before the 18th century — were often hives of activity with artisans and apprentices working in close proximity. Artists worked in bottegas or ‘workrooms.’ The studio, or study, was more readily associated with academia and originally had more contemplative connotations. The formation of the modern artist — a thinker as much as a manufacturer — shifted the concept of the studio into a place of solace.

The establishment of art schools in the late 18th century further accelerated the division between education and artistic production. This was accompanied by newly falsified divisions between applied and fine arts which have hampered institutional thinking to this day.

Intoart’s multi-disciplinary and innovative approach combines the topology of the medieval workroom with the strategies of the contemporary art school. Their studio — situated in a converted carpark in Peckham — is the engine room that fuels the organisation’s itinerant activities. Intoart have continued to grow and their reach is now far beyond the scope of a traditional studio provider, encompassing publishing, selling and educational activities as well as operating a growing collection of 3,000+ works.

So, medieval studio, art school, commercial gallery, and museum? Do Intoart’s staff ever sleep? If Intoart was an animal it would be an octopus, a shape-shifting multi-handed animal with its plethora of arms kept busy on a multitude of projects.

Structural affinities can be sought between Intoart and organisations such as Open School East and New Contemporaries who similarly offer guided support for artists. Organisations as diverse as KARST, Plymouth, Newbridge Project, Newcastle and Grand Union, Birmingham similarly offer exhibitions, studio provision and artist support. Not to mention informal and non-accredited courses such as School of the Damned and Syllabus (run by Wysing Art Centre and Eastside Projects among others).

Many of these organisational models borrow from historical educational antecedents such as Bauhaus, Black Mountain College and the Basic Design in their embrace of multi-disciplinary material-led experimentation. Yet, crucially they merge additional functions to re-imagine artist support in response to a crisis in higher education, lack of studio support and continued precarity made worse by austerity.

Intoart preceded this pedagogical turn, offering holistic support for artists with learning disabilities, and their approach — long term dialogue and advocacy — is a response to the marginalisation of the artists they support.

I’m reminded of something that the writer Joan Tronto previously wrote on the difference between caring for (hands-on care), caring about (engagement) and caring with others to mobilise and transform the world. These three forms of care — and particularly the caring with — are central to everything that Intoart does.

An Artwork is a Boomerang...

Artworks are like boomerangs, made and thrown into the world with the hope that something comes back. Artists invent and invite, and the work that they produce demands a response. What do you value? What kind of world do you want to — or don’t want to — inhabit.

Making art is fraught and complex; translating feeling into form always is. It requires both certainty and indecision, grasping at things just out of reach and it always asks for one thing in return: curiosity.

Who was it that said curiosity was like a kiss that awakened an artwork? It’s a little romantic but you get the picture. Similarly, most curators are told early on in their education that the word curating shares meaning with the words caring and curing. Perhaps this takes some agency away from the artist, but what interests me in each case is that the artwork is healed by the ameliorative qualities of visibility.

The sleepy artwork is thrown into the world with one simple demand: see me! When an artwork demands to be seen it asks for much more than your eyeballs. It asks for curiosity, conversation and dialogue. This is what boomerangs back to the artist, forming a constant loop of inspiration. Much of what artists make — that doesn’t make it to the bin — awaits its moment to go into the world and bring something back to the artist.

The book you’re holding in your hands — celebrating over twenty years of Intoart’s important work — is part archive and showpiece for these artists. It’s a boomerang, thrown into the world with the hope that opportunities come back. It makes its own demand of the reader: it’s over to you now. You curate this.

Reading through it, I’m struck by the significant amounts of love that has gone into making it possible. It asks to be cared for, cared about and cared with. The stacked canvases and piles of drawings patiently await their curious kiss from a stranger.

Exhibition view of 'A Lion in the Studio' at Copeland Gallery, Peckham. Image courtesy of Intact

A Lion in the Studio: A Very Very Very Good Exhibition

“The minute I sat in front of a canvas I was happy. Because it was a world and I could do what I like in it.”

Alice Neel

A line dances. A line meanders. A line gets tangled describing the simple ellipse of a plant leaf and is elegant describing a plate of messy spaghetti. Lines zig-zag across the page and dissolve into soft focus, unclear where to stop. Lines can be dominant, tentative, awkward, intrepid, striking, careless and refined. They can describe anger and joy, ecstatic reverie and vexed irritation. On a map, lines locate boundaries. In art, lines can set you free. Lines can leave behind physical marks and bring forward sparkling metaphors. Drawing — scribbling and sketching, hatching and smudging — transform impressions through the artist’s eyeballs, around the body’s nervous system and out through the finger and thumbs. Drawing is thought and felt.

A Lion in the Studio convenes 22 artists from Intoart who remake the world through their own kaleidoscopic assortment of painted, etched, carved and drawn lines. Over the last year or so I’ve had the great pleasure working with Intoart as a writer in residence, visiting their studios in Peckham and meeting many of the artists. I’ve undertaken workshops and the resulting conversations have meandered like the lines in the artists’ work, touching upon their ambitions, musical tastes and artistic influences. Conversations have been soundtracked by Harry Styles, Lizzo and the theme tune to Mary Poppins. I’ve asked the artists to imagine their art as a plate of food (Greggs, fish and chips, mince and Yorkshire pudding, and chicken on the bone with rice) and imagine their work as an animal (lions, cats, elephants, owls and Tasmanian devils). These seem metaphorically apt: smart, powerful, all-seeing and full of mischief. I asked each artist to imagine the biggest thing they could think of (the moon, a church and a champagne bottle) and visualise their work in a gallery asking them to articulate the subsequently effusive reviews (a very very very good exhibition).

I’ve found the artists to be an ambitious lot, demanding the art world’s biggest accolades and representation from London’s largest commercial galleries alongside international touring shows and museum retrospectives. Some of them are already there, others are on their way. Curators and gallerists reading this: get your skates on, these artists aren’t messing around. A Lion in the Studio offers a snapshot of some of the work coming out of Intoart’s studio. What follows is an account of the work of the artists that I’ve met with so far, providing a sense of the range of work being produced. It is always difficult to characterise a group of artists whose formal approaches and interests are so diverse, but it strikes me that all the artists at Intoart share something in common: a deep attachment to making, married to an indifferent disregard for the policed boundaries between art, design, fashion, performance and music.

“Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction.”

Francis Picabia

In Clifton Wright’s oil and soft pastel drawings bodies and buildings collide. In this collision, limbs are severed, re-sized, flattened and recomposed. Wright often starts with the face, flagrantly ignoring its anatomy. Eyes and mouths as big as arms, the figure becomes architectural, tangled, and morphing into abstract shapes that interlock and often teeter on the brink of collapse. Everything is in a state of being remade. On my various visits to the studio Wright shows me film stills from the Eighties film Ghostbusters, Poussin paintings and images of Classical and Modernist ruination. These disparate inspirations combine in Wright’s pictures, cooked up into an imaginative stew, a Frankenstein soup.

Christian Ovonlen’s influences are equally diverse; ranging from Ballets Russes, Japanese Kimono, Modernist costume design and mid-nineties chart music. He shows me lists of his favourite songs by year. 1991 is dominated by the peerless KLF with three singles in his list. Ovonlen’s work is rooted in drawing: feathers, flora, and dancing are frequent motifs. Typical of many of the artists at Intoart, the work is expanded and multi-layered, the imagery is often silk-screened onto textiles and displayed as wall hangings. The works are boldly chromatic, the watercolour-like dye used in the printing process compliments the lightness of the fabric’s drapery. Ovonlen has a delicate touch, the resultant works full of movement and luminosity. In the last few years, many of these textiles have been fashioned into capes the artist performs in accompanied by music. From military uniform to wizardry and superheroes; capes, cloaks and overcoats have many functional and symbolic associations. They can help us fly and render us invisible, teleport us to fantastical realms and protect us from adversity. Ovonlen’s capes add to this rich magical and artistic tradition.

Ntiense Eno-Amooquaye’s itinerant practice encompasses drawing, painting, film, performance and fashion. For A Lion in the Studio she presents a series of large silk hangings encompassing Shibori tie dye and screen print. These were made to serve as backdrops to a film that Eno-Amooquaye is currently making. Writing is central to Eno-Amooquaye’s work and often accompanies her images in written and oral form. Her imagery is flattened and articulated in thick black ink occasionally blocked out with colour. Her pictures form contemporary hieroglyphs, encompassing a personal cosmology of influences drawn from the artist’s research, travels and trips to museums. We’re rebounded between the micro and macro; monumental and mundane. Machinery, flora, costume, people and animals as well as building facias are often simplified and conjoined and joined by elliptical and lyrical phrases: ‘Life in Memory with Art and Nature’ and ‘African Bird Dynasty’. You glide over these words, rolling them around on your tongue. Eno-Amooquaye creates spaces in the middle of things; the gap between a word and its meaning, the space between images and phrases that the viewer inhabit’s with their own imagination. Her work renders the erratic and tangential, playful and melodic.

Andre Williams’s richly coloured drawings portray animals, masks and people. Fashionable street-wear, Eighties computer graphics, opulent turn of the century design and eclectic typography can also be found in his heady list of influences. Over the last few years he has expanded these drawings into domestic environments creating installations incorporating wallpapers, rugs and hand painted furniture. For the exhibition Williams presents a series of portraits of models wearing assorted streetwear taken from a fashion compendium. Each figure is depicted against a white backdrop accompanied by phrases such as ‘Disco Dance’ and ‘Lipstick Shorts’ drawn in expressive typeface. The figures are all nattily dressed in puffa jackets and gilets, floral wear and folksy knitted jumpers. Williams’s sartorial figures ape the shapes of the letters. Two armpits mirror the letter M while fingers form an upturned W. William’s work reminds us that our bodies leak meaning without intending to; we speak with our mouths shut, and say complex things with simple gestures.

The figure is central to Nancy Clayton’s soft pastel drawings, albeit with a more overt political focus. She has previously depicted American jazz musicians and more recently turned her focus on Disabled dancers. She has also worked with live dancers, producing large-scale drawings as they perform. Clayton’s work interrogates the possibilities of the body in motion. While figures such as Trisha Brown and Siobhan Davies are noted influences, Clayton has much also to say about the societal invisibility of Disabled people. In celebrating her subjects’ skills, her work offers a jubilant rebuke to the social erasure of Disabled bodies. Produced in a context where Disabled bodies are often denigrated and minoritised, Clayton offers an affirmative and defiant declaration of bodily empowerment.

In Nick Fenn’s work the body is almost always entirely absent, and he instead focuses his attention on his forays into the local landscape, depicting the locations with an impressive range of delicate marks framed by expanses of empty paper. He captures the textures of shrubbery and bark, rock and lichen with graphite, charcoal and felt-tip. Looking at these works you can sense his eyes darting around, moving up close to the various surfaces. There is a forensic-like focus, often shifting his attention from a vista into the particular details. Fenn reminds us that if we look close enough at the world it starts to fall apart. In this deconstruction another productive type of seeing emerges. This uncertain space becomes a site of imaginative projection.

Dawn Wilson’s drawings depict dapper figures dancing, travelling and being in the company of others. Churches, dancefloors and bars feature frequently, and her work draws from historic photographs of communities in Jamaica, and Mali and Democratic Republic of the Congo. Typically, Wilson covers the whole page in subtle shades of graphite depicting people and their environment with equal relish. The figures in her works are often expectantly posed with jutting arms and legs strutting moves on the dance floor or bunched up closely to capture a celebratory event. Shapes echo through the image forming rich patterns. More recently Wilson has inserted photographic representations of herself into drawn interiors, adapting the look of mid-century photographic studios. In Wilson’s work we sense a keen eye for stylistic detail; the way an earring frames a haircut or a belt pinches a dress above the waist to form a fashionable silhouette.

Mawuena Kattah works across textiles, ceramics, illustration, print and paint, drawing inspiration from family photographs as well as family and friends who sit for her. A connective thread through much of the artist’s work is an unabashed joy in being with others, sharing good food and great conversations. She has previously painted lavish portraits and her interest in patterning and colour has become more overt with inspiration gleaned from British Arts and Crafts wallpaper from the V&A and African textiles spotted at Brixton market that nod to her Ghanian heritage. A recent mixed-media image reworks a 19th woodcut wallpaper pattern by Walter Crane depicting a hunting scene with a fox running after a deer. In Kattah’s updated ink and oil pastel work, two deer repetitively appear, gleefully running alongside each other. The work depicts the world as it might be rather than how it often is. Foe becomes friend as nature’s inherent competitiveness is recast in a more carefree light.

“In this moment we must prioritise the pleasure of those most impacted by oppression.”

Adrienne maree brown

From friendly deer to hip Nineties street-wear, explorations of cultural heritage through to the politics of everyday joy; the artists of Intoart show us that claiming pleasure is a deeply political undertaking. A Lion in the Studio is, then, a very very very good exhibition. It is also an exhibition that shows us that art is a way of being in the world by transforming it through joy, tenderness, love, fun, play and community.