The text was commissioned for a monograph on the work of Lisa Trim, published by Intoart, 2024.

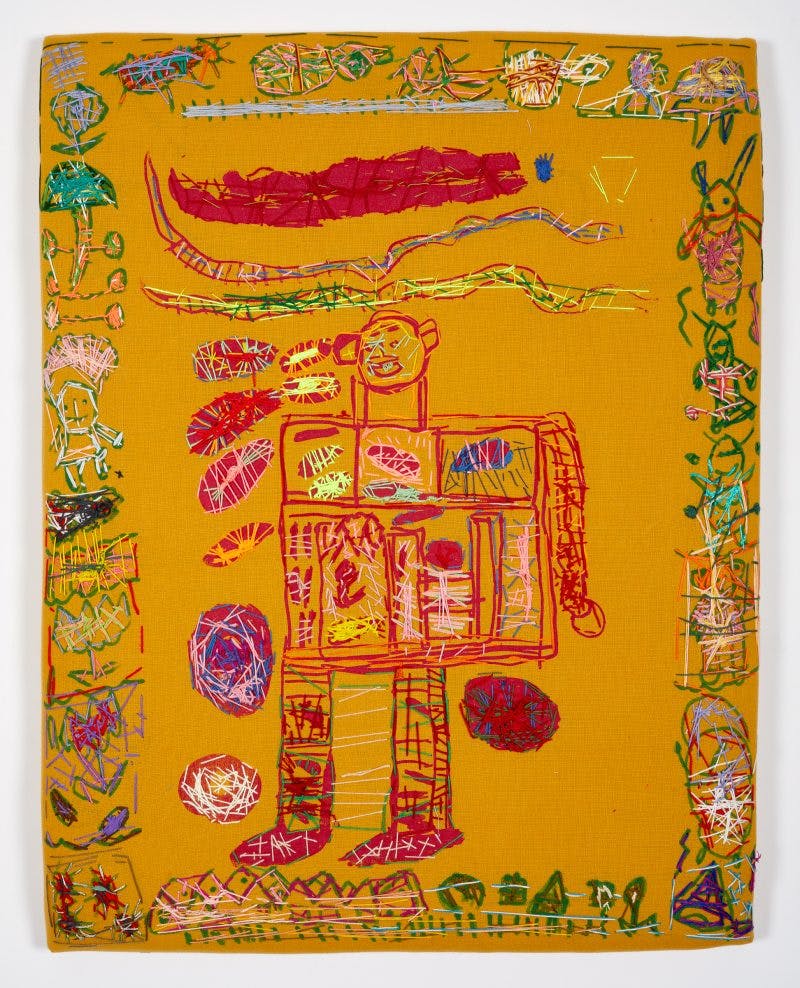

Yellow Lady in Dancing Shoes, 2023.

Reading time 5'

Some prefer to stuff their message in a bottle, a few want to shout through a megaphone while others would rather proclaim in bold type. Everyone wants to communicate something. Artists more than most. Whether it’s implicit or explicit, concealed or camouflaged, textual or textural, all art says something. Look at an artist’s line: it might make you feel exalted or agitated, warm and fuzzy or a little cold. The artist makes sense of the world by impacting on the senses of their viewer. Artists’ messages aren’t always immediately legible. Their words and images can worm their way into your mind and wreak havoc before they start making sense.

Lisa Trim’s art often contains very specific messages. For several years, the artist has developed pictograms created from her own visual alphabet: S for strawberry, F for frog, K for kettle and so on. Often the imagery is accessible while at other points slightly more oblique (E for egg sandwich is a firm favourite). Looking at Trim’s work, we’re often tasked with the role of the detective; looking becomes a form of decoding, parsing the image for clues. It takes me a while to read the diminutive green triangles that sit jagged against a blank background as blades of grass.

Pictograms have a long history. In pre-literate societies, we told stories through images. Images are instructive in many ways but we need to know how to read them. Trim updates this ancient tradition and infuses it with her own lyrical and deadpan imagery. The effect is full of mischievous and incongruent juxtapositions: sunflowers, owls, carrots and grass. Trim often takes objects out of context, simplifying and amplifying their forms against plain and colourful backgrounds. Colours pop. Shapes zing. My eyes remain transfixed. Trim’s work is full of vivid and lucid detail, the decorative pattern of a butterfly’s wing or lovingly articulated rabbit’s fur.

In her wondrous practice, Trim tackles high and low culture, the close at hand and the further away. Previous works have explored historic costume, animals and nature, flowers and cryptology, as well as the human figure. Her relationship to the figure is often more experimental in tone, the body pushed to a point of stylised abstraction. Her mark making can veer from the incisive to more elaborated and embellished forms. She pushes objects around; forms are exaggerated and reworked so that they make their own kind of sense.

In more recent works, a fascination with pubs has surfaced, where Trim explores pub signs and their heraldic vernacular. This imagery permeates many of the artist’s fabric works. Experimenting with couching, stitching and appliqué, the textiles have significantly expanded over the last few years. Fastidiously building up imagery over many weeks in the studio using screen-printing, Trim further embellishes the textiles, using the needle and thread the way one would use a pencil. Felt and fabric are appliquéd to dyed linen and further elaborated with embroidery that animates the surface with colourful hatching. A scrumpled fabric off-cut might become a flower, a patch of felt a flower bed. Flowers in the shape of hearts are scattered throughout. Imagery is sketched freehand with different colours and thread tracing the forms’ contours. Trim has an eye for luscious colour relationships: lilac, crimson, Naples yellow and viridian green permeate many of the pictures.

In works such as ‘Yellow Lady in Dancing Shoes’ and ‘Green Girl in a Skirt Playing’, both 2023, Trim tackles the motif of a lone figure. The anonymous character appears tectonic and machinic, merging human with robotic elements. I’m reminded of Eduardo Paolozzi’s hybrid bodies, distended and elongated organs merging into hardware. The edges of the canvases are heavily decorated and frame the action in the centre of the picture. The yellow lady (actually red on a mustard background) is lifted from a previous drawing called ‘Square Body’,2022.

Shapes surround the body, variously evoking sweat and speech bubbles. Perhaps they’re spotlights. Maybe they’re pebbles. Here I am again, playing detective attempting to decode Trim’s particular iconography, looking for things that might not be there. Whatever the origin of the shapes, they furnish the painting with detail that animates the figure. The embroidery – with its short bursts of colour – electrifies the imagery like static on an old TV. We glimpse at things half-formed as they move around the artist’s imagination and slither their way into the picture.

Imagery of home abounds in Trim’s work. We see many variations on the theme: house with windows, a home with a garden, a domed house, rows of houses with their chimneys and arching roofs abstracted and repeated into a pattern. Sometimes this imagery becomes grand and regal. The house transforms into a castle or temple. In Trim’s work, the house is a space of living and making, life and art inextricably bound. This domestic theme is pronounced in works such as ‘A Patchwork of Home’, 2021, combining a series of embroideries. The use of patchwork evokes generational conversations and traditions passed among family members, of family heirlooms gifted between parents and children. These highly skilled objects are often authorless, collaborative endeavours mended and maintained through whole lifetimes. Craft is tacit knowledge. It is a knowledge of the body, a language beyond words, felt as much as understood.

Trim asks us to look hard. As the viewer becomes a detective, we’re tasked with looking and decoding for clues hidden in plain sight. Of course, the artist’s message isn’t always immediately legible and not always entirely resolvable. Trim keeps us on our toes: she is the yellow dancing lady. She is the girl in the green skirt playing. She is the gentle figure. She is the owl. She is L for Lisa Trim. She is all of this and more.