The text was published in a monograph of Lisa Contucci's work, published by Intoart, 2024.

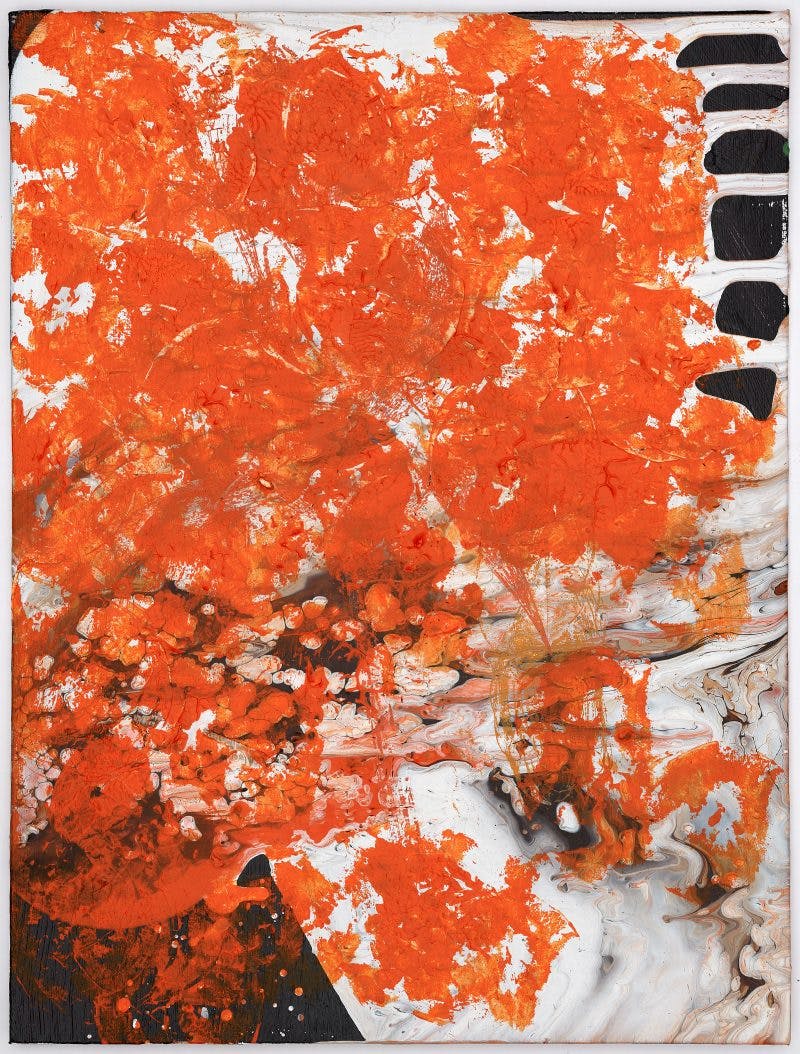

Lisa Contucci, Forming, 2023

Reading time 5'

Painting is a funny business. In a world of abundant technologies, it is a particularly inefficient form of communication: messy, expensive, space-dependent and time consuming and, yet we are consumed by its particular poetry, even after all these years. From daubing caves to decorating cathedrals, painting has been with us since the dawn of our species, with generations of humans materialising their thinking through the process of making images with pigments.

Lisa Contucci is an artist invested in the funny business of paint. Many of Contucci’s paintings start life on the artist’s holiday trips visiting her family in Italy, where she transforms impressions of travelling through the landscape. Her paintings embody the exhilaration of encountering sweeping vistas of forests, waterfalls and meandering roads that are invoked through layers of paint that create glorious, gestural, effervescent, sculptural and resolutely material paintings. These are paintings as moments and concretised memories.

Watching Contucci paint is quite something: she’s a kinetic whirl, slapping and hitting the painting with various implements. Contucci uses a varied toolkit to produce a litany of marks, including radiator cleaners, old toothbrushes, paint rollers with bits hacked out of them, plastic bones and combs. I could go on. She uses the things around her to make paintings that point towards subjects further afield, like a mountainous terrain captured by a battered potato masher. In Contucci’s work, utility and majesty coalesce. Picture the headline: Sunday roast meets scenic sublime.

Paint is variously poured and painted, transferred onto the canvas in myriad ways and often made sculptural by bulking it with saw dust, sand and plaster. The implements create print-like marks that fill the imagery with energised repetitions and patterns. Top and bottom become displaced as Contucci frequently moves the painting around. While the process appears frenetic, the artist is deep in creative flow, every move a considered painterly conversation. The surfaces of her canvases, works on paper and wood panels are variously scribbled on with pastels and pencils and scrapped, daubed and smeared with bright blotches of colour. The surfaces are environmental rather than representational, paint is sedimented and subject to vigorous reworking invoking the complex geology of the land.

In works such as ‘Journey to Nanna’s (1-3)’, 2023, Contucci scales up her more intimate works on paper and board. In these paintings, split over multiple canvases, the mark making is loose, with large areas of unprimed canvas left bare. The abstract forms create an emergent grammar with isolated elements creating a conversation across the image. Orange, sky blue, ochres and oranges pop against the unprimed linen. While it is tempting to pin the work to a particular location, it is perhaps felicitous to let the work’s poetry do its thing.

In works such as ‘Warm Touch’, 2023, she adds string to the surface, partially tacked on with paint. The surface of the paint is reworked with a pen so that the swirling mass of paint becomes indented with calligraphic marks. The work is full of these formal tensions: liquid and concrete, watery and buttery. This is an art of suggestion: concrete, wet moss, candy floss, waterfalls and fluffy clouds. There is a seasonality to the work, evoked through texture and colour that animate their associative pull. Her paintings can variously call to mind blustery early autumn afternoons and warm hazy summer evenings. My mind wanders off as my eyes remain glued to their compelling surfaces.

The work often veers between figurative evocation and more abstracted colour and form, each painting betraying an impressive amalgam of different marks. Take ‘Landscape with Circles’, 2022, which encompasses a range of painterly gestures on an unprimed, unstretched canvas. Forms that could denote shrubbery and clouds are punctured by circular prints that forcefully push the painting into something more direct. Contucci take the experience of being in and moving through the land and relates that to the process of painting. It’s less about representation and more an act of bodily and painterly transformation.

In ‘Sun Rises’, 2023, the painting is first built up from pastel and then with thicker acrylic and plaster. Parts of the painting have started to crack, groaning under the sheer weight of the paint. These paintings are tactile and sensual. The top layers of paint are poured, dripping in different directions suggesting that the panel has been continually moved throughout the process of its making.

Drawing remains integral to Contucci’s process, and she often speedily works up ideas in concertina sketchbooks with intuitive mark making and colour combinations. This approach foregrounds sensations, the artist’s hand meandering like the Italian roads. This creative flow is crucial as the drawings and paintings become of the body, intimately connected to her hands and nervous system. Contucci reminds us that art is about putting how we feel about things into materials.

During the studio visit, Contucci frequently caresses the paintings as she shows them. Her hands glide over the coagulated paint, as if reliving the process of making. These paintings remain active material encounters. Contucci’s paintings and drawings are never truly finished, each image is a snapshot that merges an impression of the landscape through the artist’s body. In looking at these paintings we’re reminded that the act of making is optical, gestural and neurological – the world is sensed through the eyeballs and made sense of by the body and the brain. It’s the artist’s sense of the world in material form. It’s feeling made concrete.

Contucci belongs to a genealogy of painters such as Sam Gilliam, Howard Hodgkin, Frank Bowling, and Helen Frankenthaler, who have invigorated abstraction. Like these artists, Contucci invests in the funny business of paint, bringing a renewed energy to the inefficient and messy. She brings a poetic tenor to the ineffable and the undefinable act of applying pigment to cloth (paper and wood). Paul Valéry once said that bad poetry vanishes into meaning. Contucci’s paintings do the opposite: they’re generative sites of meaning-making that continue to resonate in myriad ways, animated by the imagination of audiences that encounter them.