First published in Art Monthly in 2019 in response to Reinhard Mucha's exhibition Full Take at Sprüth Magers.

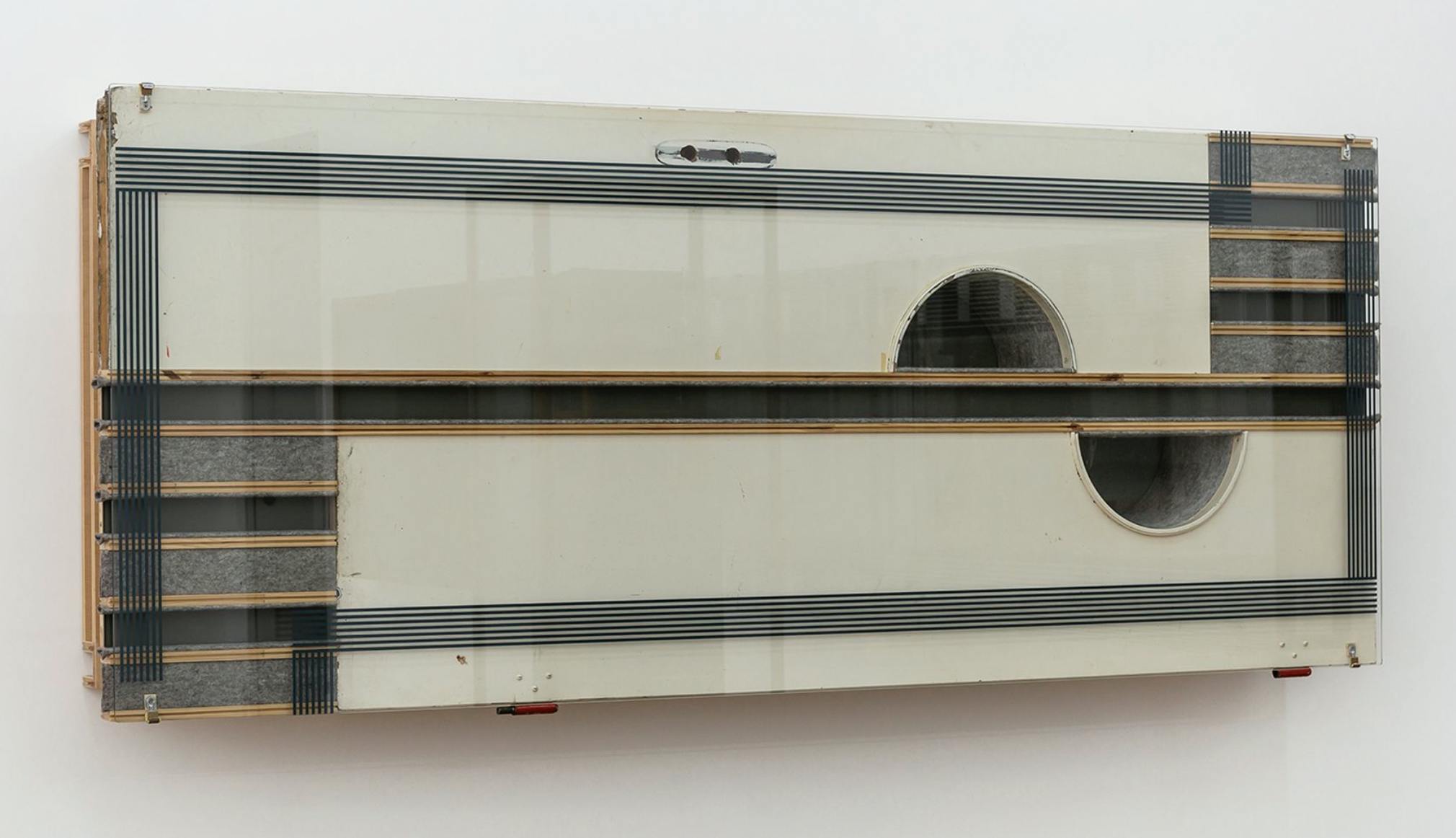

Reinhard Mucha, HameIn, 2014 ©muchaArchive

Reading time 5'

Packing material, felt, linoleum, train sets, formica, doors, cabinets, foot stools and coal bricks. The domestic abuts the transportive in Reinhard Mucha’s practice. Listing off his lexicon of everyday materials only gets you so far in parsing these works for meaning. The artist cuts, stacks and collages these materials into layered and knotty assemblages. Often incorporating elements of his own past, he includes documentation of previous works that are then remixed and formed into new configurations. Elaborate framing devices, vitrines and felt-lined displays; ‘Full Take’ – Mucha’s first solo exhibition in London since 1997 – riffs on museological display and puts it in the service of a certain opacity.

Take HAMELN, 2014, which encompasses a wooden door that has been cut in half and placed on its side. A bold geometric line cuts the work down the middle. The door has been knocked off centre and the circular window has become two semi circles that suggest train tunnels or plumbing. In a typical gesture, a relief is presented under glass clamped at the top and bottom and painted with fine grey lines that interact with and frame the forms underneath. The side of the work is left open, revealing the innards of its fastidious construction. The attentiveness extends to the wall labels with the work’s material list presented in the order it appears in the work. This systematic ordering suggests a conceptual horizontality, with each component bearing equal significance.

Schuld, (2019) 2015 incorporates a model train set that Mucha has again cut in half. Wood is stained and worn from years of use. Packing material used to transport the work has been placed in vertical lines on either side to create an asymmetrical composition. As in other pieces, it is framed under glass and painted with fine grey lines that recall geometric abstract painting and municipal graphics. The intermittent recesses form a shallow depth of field, creating multiple layers and the grey lines simultaneously frame and conceal. We move our body and eyes to scan the work’s myriad details – its surface taking on a sculptural as much as pictorial quality.

Oderin/Untitled (Männer Frauen), (1987) 1987/1981 encompasses paintings on glass, folded into the corner of the room and mounted onto felt panels. The paintings incorporate the words ‘man’ and ‘woman’ in a sans-serif white typeface on a black background. The V-shaped installation reflects the paintings’ respective surfaces onto each other, further confusing their legibility. They are joined by a large squat plinth covered in grey felt propped up on footstools. The sculpture creates a narrow corridor making it difficult to view the words in their totality. Separated into their constituent parts, the work undermines our ability to read it. This oscillation between form and function, looking and the inability to comprehend articulates much of Mucha’s intentions.

Untitled (Wand – Kunst – Und Museumverein – Wuppertal – 1978) / Untitled (Isolde Wawrin — Ohne Titel (Object), 1978), (2019) 1985 is a temporal Russian doll, incorporating multiple elements from different eras. Floor plans and photographs of an artwork that Mucha contributed to an exhibition while he was a student at Düsseldorf Academy is presented in a wall-mounted vitrine-like display. This earlier work takes the form of a wall, built over a series of windows in the gallery, that hosted his fellow student Isolde Wawrin’s paintings. For this exhibition, the work is newly joined by Wawrin’s painting, which is framed above. We can draw parallels between Mucha’s wall and a raft of conceptual practices intervening in the structure of the gallery. While this earlier work made its labour invisible and the artist’s subsequent work demonstrates his astute craft, there is a continued desire to call attention to the mechanics of exhibition display.

Mucha’s practice is highly hermetic and reflexive. Writing about it feels like trying to lasso and restrain a wild horse – it slips and slides under my grasp. Where does each piece begin and end? Where do we place the frame? Ultimately the work demands attention in a world of inattention. With their glass surfaces, they reflect our gaze back at us and situate our bodies in relation to the environment – they host and are hosted by their context. They ask us to look and keeping looking. In the context of a film, a full take suggests the final filmed sequence of a particular scene. One senses that a Mucha work is never finished; seeing and making can be exhausting but it is never exhaustive.